The Marianist Death Penalty Team encourages people to consider the Christian mandate to love and forgive.

By Shelly Reese

“We, as the Marianist Family, because of our belief in the sanctity of all human life and in the dignity of all persons, pledge ourselves to prayer, education, reflection and action to abolish the death penalty. This practice is unjust, inhumane and inconsistent with the Gospel message. By our witness we seek to change hearts and minds concerning this injustice.”( From the mission statement of the Marianist Social Justice Collaborative’s Death Penalty Team)

In the cab of his crane , Bethlehem Steel worker Bill Pelke prayed. He cried. He thought about his grandmother: her faith, her gentleness, how she loved to tell Bible stories to children. In that moment, 50-feet above the foundry floor, Pelke forgave the girl on Death Row who had killed his grandmother.

“Forgiveness is so misunderstood,” Pelke told students at a gathering at St. Mary’s Univer sity and Central Catholic High School, both Marianist schools in San Antonio. “People think if we forgive someone we’re condoning what they did. But forgiveness is a selfish act. When Jesus tells us to forgive someone it’s not for the sake of the bad guy, it’s for us. It takes the millstone off our neck.”

Today Pelke is a member of Journey of Hope, an organization led by family members of murder victims, as well as families of Death Row inmates and those who have been executed. Individuals who have been exonerated also have found solidarity with the group. Journey of Hope conducts public education speaking tours and addresses alternatives to the death penalty. In October, the Marianist Social Justice Collaborative’s Death Penalty Team hosted speakers from the Journey of Hope as they wound their way through Texas, the state with the highest rate of executions.

By bringing that message of healing and forgiveness to students and faculty at Marianist schools, Death Penalty Team members hope not only to educate others about the immorality of the death penalty but also to encourage them to contemplate the Christian mandate to love and forgive.

Marianist Sister Grace Walle, Death Penalty Team chairperson, notes, “These stories are about pain and suffering and forgiveness. As a listener, it’s a God moment.

“On one level, it’s an educational moment about the death penalty,” says Sister Grace, campus minister at St. Mary’s Law School, “but at the heart of it, listening to these people makes you think: Where is forgiveness in my life?”

THE MARIANIST PERSPECTIVE

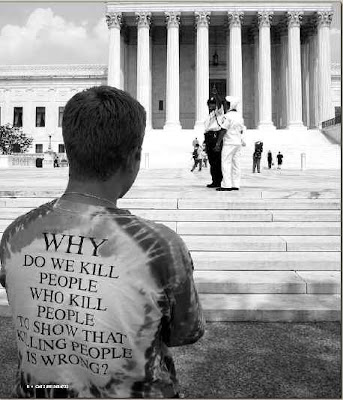

Wearing a T-shirt that reads, “Why do we kill people who kill people to show that killing people is wrong?” Marianist Brother Brian Halderman, a founding member of the Death Penalty Team, explores the contradictory nature of the death penalty.

“Scripture calls us to be our brother’s keeper — to live a life of compassion and forgiveness,” says Brother Brian. “I don’t see the logic of using homicide to deter further homicides. The death penalty creates more victims, more pain and more violence.”

People oppose the death penalty for many reasons. For some, it’s a miscarriage of social justice. As a lawyer, Marianist Brother Frank O’Donnell, a Death Penalty Team member, has witnessed firsthand the many inequities of the justice system. Poor people are at a disadvantage, he says, and the system of incarceration promotes violence rather than reformation.

“People on the outside are quick to paint inmates — particularly those accused of murder — with a broad brush and to write them off as members of society.

“Jesus and the Gospel teach us to have a high regard for life,” Brother Frank says. “It doesn’t say a high regard for some life. It’s a high regard for life.”

Lay Marianist Bob Stoughton, who worked with a Dayton-based group against the death penalty for more than 10 years before joining the MSJC team, says his opposition is rooted in Catholic social teaching and in a gut feeling that capital punishment is wrong.

“If it’s wrong to kill, then it’s wrong for the state to kill,” he says. “Catholic social teaching professes the sanctity of life.”

Others decry the system’s failings: Capital punishment is expensive, arbitrary and an ineffective deterrent. What’s more, there’s always the risk — particularly when a defendant is poor and cannot afford adequate counsel — that an innocent person may be convicted and sentenced to death. Since 1973, 124 Death Row inmates have been exonerated. At the same time, serious questions have been raised about the guilt of some of the 1,099 people put to death since 1976.

A HEART THAT HATES CANNOT HEAL

In opposing the death penalty, the MSJC Death Penalty Team has focused its energies on moratorium campaigns in five states: Missouri, Ohio, Texas, Maryland and California. As part of that effort, the team supported a rally and a prayer vigil last September at the Ohio statehouse in Columbus. The event drew more than 200 protestors. Two weeks later the team sponsored several stops on the 17-day Journey of Hope campaign through Texas.

In taking a stand against the death penalty, speakers for the Journey of Hope agree on one essential point: Another killing will not restore their loved ones.

“I came to understand that God’s sense of justice is restoration,” says Journey of Hope speaker Marietta Jaeger-Lane, whose seven-year-old daughter, Susie, was kidnapped and murdered. “The death penalty is revenge.”

In sharing their stories of loss, rage, healing and forgiveness, Journey of Hope members wish to convince listeners that capital punishment, far from resolving the problem, merely perpetuates a cycle of violence.

“Timothy McVeigh’s execution didn’t bring me any peace,” says Bud Welch, whose daughter, Julie, was murdered, along with 167 other people, in the Oklahoma City bombing. “I’ve spoken to a lot of family members since and they’ve said it didn’t help them the way they thought it would.”

Today, Welch travels around the world with the Journey of Hope speaking out against the death penalty. He admits that in the immediate aftermath of the bombing, he wanted McVeigh executed. But he knew that wouldn’t bring Julie back. As he learned more about the anger and desire for revenge that had fueled McVeigh’s attack, he came to recognize what revenge and hatred can do to a person.

“You have to get rid of the rage before you can heal,” he says.

RELINQUISHING THE BURDEN

Welch still grieves for his daughter. “When you bury your child, you bury them every day in your heart,” he says. Healing hasn’t diminished his loss, but it has enabled him to move forward with his life without a heart blackened by hatred.

That’s a sentiment Jaeger-Lane echoes more than 25 years after Susie’s death.

“Just because you forgive doesn’t mean you’ve forgotten,” she says. “It’s precisely because you will never forget that you must find a way to go on in a healthy manner. Jesus still had his wounds when he rose from the dead.”

Because of the pain, forgiveness can be a long and difficult process. Welch admits he still struggles at times.

“Forgiveness is not an event,” he says. “It’s a process and it happens for the rest of your life. You have moments when you revert back and think, ‘that bastard didn’t deserve to live,’ but you get past those moments. I’m not sure that people have to forgive to heal, but I’ll tell you, when you do, it sure makes you feel better.”

Jaeger-Lane compares her experience in learning to forgive with an alcoholic craving a drink. “I had to take it minuteby- minute,” she says. “I had to think, ‘I can get through this minute without hating this person.’

“Forgiveness is not easy,” she says. “It takes daily, devoted discipline. My mind would go one way and I would have to call myself back. I had to remind myself, ‘This is who I am, and this is what God wants me to do.’

About a month after her daughter’s abduction, Jaeger-Lane bought a Bible and started reading it. “I realized I was called to pray for my enemies,” she said, and so she began to pray for the nameless man who had taken Susie. “I’d pray things like, ‘if he’s traveling may he not have car trouble’ or ‘if he’s fishing may he have a good catch.’ Little things. But the more I prayed the easier it got.”

That’s a powerful message for listeners who can’t imagine praying for someone who had violated them in such a ruthless way.

“It was very inspirational to listen to her,” says 19-year-old Sean Stilson, a sophomore at St. Mary’s who attended the Journey of Hope session. “She initially reacted the way any person would, but through God’s grace she learned to forgive. It puts forgiveness in my own life into perspective. It’s a reminder that there are people with problems that are so much bigger than my own. If they can forgive, then I can forgive the little things in my life.”

Article taken from

Alive - Marianist Culture, faith and community

No comments:

Post a Comment